(This article first appeared in the fourth issue of Logbook, c.1997.) (A PDF Copy is available here)

Only two years before World War II started no RAAF aircraft of any kind were based in Western Australia, but there was an Air Force.

Not until March 1938 did the Royal Australian Air Force become permanently based in Wester Australia. Before that only a handful of RAAF aeroplanes had paid visits to Australia’s western third, and then only for a pitifully few days at a time. Until the RAAF Base at Bullsbrook was commissioned in March 1938 the only permanent group which gave Wester Australia even the semblance of military aviation was ‘Brigadier Martyn’s Air Force’. Officially it was known as the Army Cooperation Section of the Aero Club of Western Australia and its task was to fly in cooperation with the Australian Militia Forces in Wester Australia under the command of Brigadier Tim Martyn.

The RAAF did not have a base or any permanent forces in Western Australia simply because the Commonwealth government could not afford them. Up until 1928.the strength of the RAAF was so tiny that its bases in Victoria and New South Wales were more than adequate. In that year Air Marshal Salmond of the Royal Air Force toured Australia and wrote a report for the Commonwealth government setting our how the Air Force should be developed, including stationing permanent military aviation forces. in Western Australia. The Great Depression, which began the following year, made Salmond’s plan impossible to implement.

The Aero Club of Western Australia also suffered greatly because of the Depression. Even with the government subsidy, operating a flying school and aero club was an expensive business and it was difficult to encourage people to take an interest in flying. The. club was subsidized by the Commonwealth government which wanted to foster a sense of airmindedness in the general community and to encourage the growth of a large body of men with flying experience which could be tapped in times of national emergency. The aero clubs were well aware of this national obligation and most people at the time took very seriously the combination of the pleasure of flying with the national obligation which went with it.

All young men in Australia knew about their national obligation because there was a system of compulsory military raining under which they were compelled to undertake regular military training and attend annual military camps. This was little questioned and considered a necessary if sometimes odious part of a person’s civil duty. This system was abandoned in 1931 however, another victim of cost cutting during the Depression. It was replaced by the voluntary militia which still attracted large numbers of young men to its ranks.

All these factors came together to create Brigadier Martyn’s Air Force. Aero Club members wanted to encourage flying and do something to justify the support the club received from the government. Brigadier Martyn wanted to improve the quality of training his volunteer soldiers received and the RAAF was nowhere to be seen. Perhaps the Aero Club could help to fill the void. There were enthusiastic young Aero Club members keen to take part and the club saw it as a good opportunity to encourage flying. The government provided no official support whatsoever, and the pilots involved in the volunteer activity had to hire the aeroplanes from the Aero Club at their own expense, although the club reduced the hire charge to 10/-.an hour for this activity.

The official suggestion to form the Army Cooperation Section first appeared in a club report in April 1932. Government officials were interested in the project but unable to give any assistance so the club planned to set up a section.of pilots under the command and instruction of aviation stalwarts in Western Australia such as Sydney Briggs and Val Abbott. As well as helping to train militia troops by using an aviation element in their manoeuvres, the section would give pilots and observers more useful training than they had previously experienced.

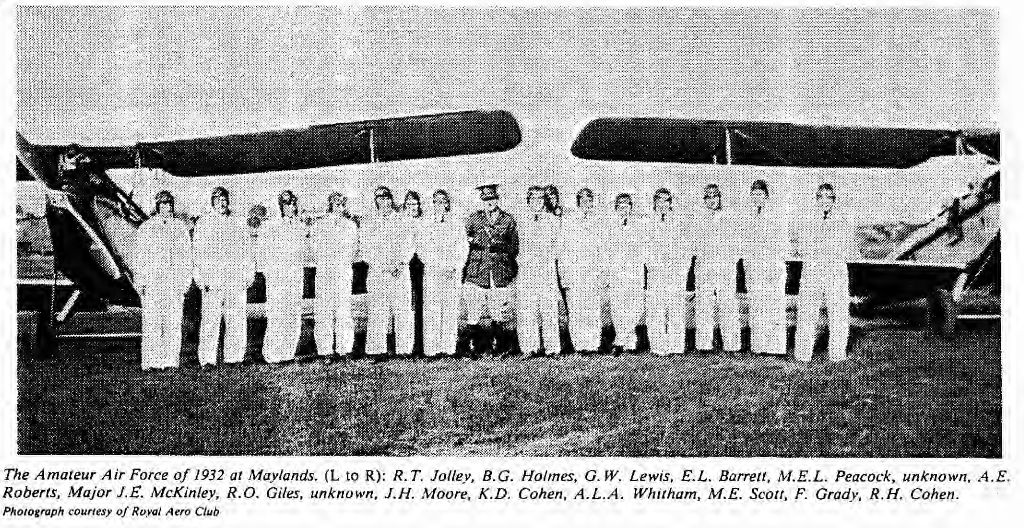

In September 1932 the proposal was discussed in detail at a special meeting of the club. Initially it was planned that only about half a dozen pilots would be selected for training in militia aviation but the proposal was received so enthusiastically that 20 pilots were enrolled for general training, with a nucleus of militia pilots to be selected from them. The actual arrangement of the Army Cooperation Section does not appear to have been very formal, however, and who flew and when they flew must have depended on who could make themselves available.when the militia needed them and who could afford the expense.

For the first couple of years Brigadier Martyn’s Air Force was quite active. Its members engaged in training in the air and on the ground. It also flew with militia forces in exercises around the Perth area and on a couple of occasions it took part in the annual Militia Camps held at Northam.

In the Perth area two of the Army Cooperation Section’s most important involvements were in large scale war games. At the Battle of Canning Bridge a force from Fremantle and an opposing force from Perth marched to meet at the Canning River Bridge just next to the Raffles Hotel and both sides and their air support enjoyed a convivial evening at the hotel before the battle. Martyn’s Air Force supplied a DH60 to each side, one flying with a streamer flying from a strut and the other without. These aeroplanes flew continuous reconnaissance missions keeping their side informed of the opposition’s movements. At the Canning River they bombed the bridge with flour bag bombs and also spread them liberally over friend and foe alike. The whole exercise was a huge success and very enjoyable. It was also reported widely in the national press.

A couple of years later, in 1936, a similar exercise occurred on Rottnest Island just off the coast from Perth. On this occasion a couple of aeroplanes from the Aero Club took part in an exercise simulating an invasion of the island.

In the first operation.of the day one Moth flew low around the island while the other performed a few loops and stalled turns to attract the opposition’s attention. While the troops were distracted the first Moth flew in low and delivered.a few well placed flour bombs before the troops on the ground knew what was happening. Later in the morning the air force dusted the troops with more flour bag bombs and were back at the Aero Club at Maylands in time for lunch.

The Militia camps at Northam were somewhat more arduous, though probably just as much fun.. In March 1934 two Aero Club Moths flew to the landing ground at the Northam Racecourse to take part in several days flying. The weather was atrocious and although the Moths had a difficult enough time flying to Northam the rest of the men involved had a much worse time battling to get their cars through floods and washaways. The flying was generally very successful and much of the time was taken up in practicing reconnaissance with ground troops. The Moths had radio transmitters, which had been made by local wireless enthusiasts, fitted in the front cockpit and they could send messages about the troop movements they saw from the air. On one occasion the section was detailed to locate a lost militia unit in an area of several square miles and they had found it and sent the information back to headquarters within I2 minutes.

Members of the section camped.in racecourse buildings and were invited to most of the clubs in the town during their stay so they had a very social time. The only mishap of the outing occurred on the landing ground when VH-UAO started to bog and nosed over during a take off run, but the pilot cut the ignition and only a little damage occurred which was fixed on the spot. At the end of the camp the section returned to Perth with the grateful thanks of the Militia.

In March 1936 the Army Cooperation Section returned to the Northam Militia Camp for eight days. The party included eight pilots, eight observers, a ground engineer and cook and signaller. Again they occupied buildings at the Northam Race club. The first two days were devoted to flying practice and ground instruction. The next two days the men carried out signals exercises using one Moth with a wireless transmitter fitted in the front cockpit. After that they flew in co-operation with ground troops on reconnaissance missions and on the final day they took part in a simulated artillery shoot.

Official reactions to Martyn’s Air Force.were.mixed. Although the Army was keen on the idea it could do nothing concrete to help except utter its thanks. The Air Board was hampered by lack of funds and the desire to eventually establish a RAAF presence in Western Australia. However, after some discussions in early 1934 the Air Board decided to invite members of the Aero Club to join the RAAF Reserve. Joining the Reserve conferred no advantages on Aero Club members but it was about the only way that the RAAF could show some support for what the club was doing. There were no uniforms or special privileges but it gave the Aero Club a feeling that its actions were useful and appreciated. There was one unexpected but appreciated benefit because Reservists were enlisted with the rank of Sergeant and able to set up a mess which, since the Aero Club was on Maylands Aerodrome which was Commonwealth property, made it immune from state liquor laws.

On those occasions when the RAAF did visit Western Australia the Reservists were invited to come out and help. In October 1935, for example, when seven visiting RAAF aeroplanes visited Western Australia, the reservists were put to work washing down the travel stained aeroplanes and polishing their aluminium cowls for a flying display.

Earlier in the same year three Westland Wapitis from the eastern states had spent a few days based at Maylands Aerodrome to work with militia forces. During their stay a number of Reservist pilots including Bob Giles and George Lewis flew the Wapitis from the back seat to give them a little experience at flying service aeroplanes. Each spent about half an hour in the air learning the feel of the control and practising some simple manoeuvres, and they were generally praised for their flying abilities.

After the first few years enthusiasm for the Army Cooperation Section waned. One reason was because in August 1934 the Commonwealth government finally approved plans to set up a permanent air base in Wester Australia and station a squadron there.

The site for the military aerodrome was selected at Bullsbrook north of Perth and work started on constructing the necessary facilities in 1936. The first aeroplanes belonging to the squadron arrived there on 17 October 1937 and after that the strength at the base built up quickly. With the increasing strength of the RAAF in the west there seemed less need for the Aero Club to provide the Militia with experience in co-operating with aeroplanes. Perhaps the major cause for declining interest was the growing conviction that a major war was coming and the most importing thing aero clubs could do was train pilots to take their place in that war. The Aero Club put almost all its energies into attracting and training pilots and by 1938 had three branches operating in the country as well as its main base at Maylands. Between 1936 and 1937 the Aero Club more than doubled its flying hours, almost trebled the number of pilots it trained and increased its fleet of aeroplanes from four to seven to cope with the demand.

The end for the Army Cooperation Section came in mid-March.1938. On Thursday 10 March No 23 (City of Perth) Squadron arrived in Perth and paraded through the streets before moving to RAAF Base at Pearce. Five Demons and an Anson arriving from Melbourne flew in formation over the city before flying on to the base to make up the full compliment of squadron aeroplanes. With so much military air power in the state the Aero Club could contribute little of value.

There was one last action however. The following Saturday the Army Cooperation Section carried out manoeuvers with the militia by delivering a couple of air raids to a supply convoy in the Canning Bridge area. Again the men on the ground were bombarded with flour bag bombs and afterwards officers of the militia unit entertained the pilots at lunch at the Raffles Hotel. It must have been a delightful and very social conclusion to a sidelight of military aviation history.

For over five years Brigadier Martyn’s Air Force had provided a service which was unique and necessary for the military forces in Western Australia. Although it may have seemed insignificant in the scope of world events it was a contribution to the preparations Australia was making for the coming war. But by March 1938 things were starting to get serious. The newspaper that month announced that Hitler’s troops had begun their invasion of Austria. For some one-time members of the Army Cooperation Section war games would soon take on a much more authentic tone.