During the early 1930s the multi-place twin-engined long range fighter concept became popular and the first of them was the Potez 63 series, developed in response to a French air ministry requirement of 1934. The prototype first flew on 25 April 1936 but it was damaged in a crash landing and the second prototype, a 630.01, did not fly until March 1937 due to delays caused by the nationalisation of the French aircraft manufacturing industry. Although slightly underpowered the 63 series had fair performance characteristics and good handling, making it popular with pilots.

Plans were quickly developed for a wide range of variants including day fighters, night fighters and a light bomber. The Potez 637 was designed as an army co-operation and reconnaissance version, fitted with a ventral gondola for the observer, to give France something like a modern aeroplane and, although the prototype flew in mid 1938, it was a stop-gap and all 60 were delivered by September 1939.

The Potez 63.11 was a more advanced reconnaissance version with a redesigned fully glazed nose and a revised mid section although the wings and rear fuselage remained the same. The prototype flew on 31 December 1938 and it was rushed into production with plans for 860 to be in service by May 1940. Over 1000 were ordered and perhaps 900 were made and, by the time of the German invasion in May 1940, several hundred had entered service. However the spares situation was so desperate that many never flew operationally and many more were fitted with temporary wooden propellers that reduced their performance. At the same time, many were fitted in the field with additional armament including rear-firing machine guns to improve their straffing power.

In operation the 63.11s proved to be very vulnerable to enemy attack and needed fighter protection, though they rarely had it. Pilots learned to use the type’s agility to fly low to avoid air attack but that made them more vulnerable to ground fire because they lacked armour and self-sealing fuel tanks. The 63.11 suffered more heavily than other 63 series types and by June 1940 over 200 had been lost in action.

Despite their devastation during the Battle of France the 63.11 remained in production after the French surrender. They were flown by German, Rumanian and Italian air forces for training and liaison and in Vichi and Free French service. Despite its deficiencies the 63.11 was an excellent aeroplane in many respects and its main misfortune was that it was rushed into service under conditions where it suffered from almost overwhelming aerial domination that did not allow it to demonstrate its full potential.

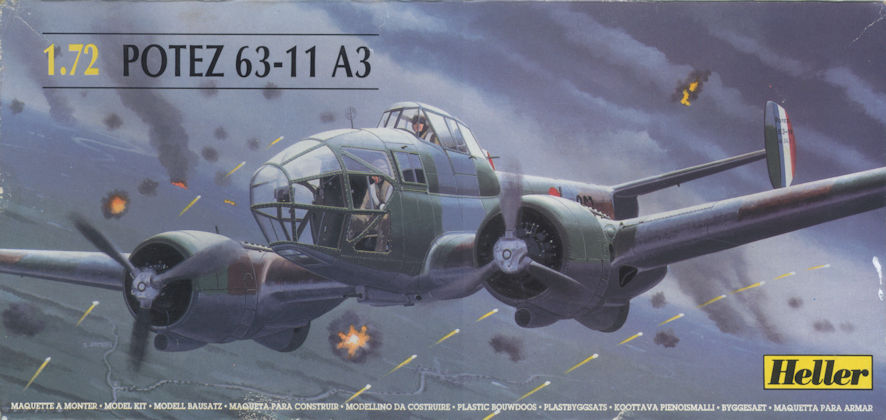

This kit comes from the golden age of Heller in 1968. They were producing kits of relatively obscure French aeroplanes, most of them from the period leading up to World War 2 when the French aviation industry was turning out a wide range of aeroplanes, none of which would fare well in the coming war. Many might have become famous had not the French defense collapsed so quickly and completely in May and June 1940.

Like other Heller kits of this period the detail would have been considered very good at the time but now seems relatively primitive. The surface details is generally delicately raised and most Heller kits have in common the use of many separate little transparencies that seem designed specifically to drive modellers insane in trying to get them to fit properly. The detail is nice and delicate and everything goes together with little fuss. If the old Aviation News plans are anything to go by it is quite accurate

The glasshouse nose and big cockpit canopy allow lots of space for detailing so it is a pity I couldn’t find anything in the way of good references showing the insides of the 63.11. Consequently this was another opportunity to fall back to Plan B, assisted by the fact that the French tended to paint their interiors a lovely dark shade of blue grey. Getting all the little clear bits into place was a real pain and the pity is that in their obsession to make life as difficult as possible for the modeller they make some of the cross bracing panels for the nose much wider than they were in real life, detracting a little from the sense of fragility the nose should have. These days kit makers would provide a much larger glazing for the nose to allow the modeller to make it more realistic but unless I could find something in the spares box (which proved futile) or to mould a new nose, there wasn’t much that could be done but whinge after the event. The other disagreeable aspect of so much clear plastic is that it all has to be masked, but some evenings there isn’t anything on the television anyhow…

The undercarriage can be made to fold up into the nacelles but the idea didn’t appeal to me the way it would have if I had made this kit when it first came out. The kit goes together with little fuss, there is the usual trailing edge thinning, seam reduction and a little bit of filling here and there but none of it is a drama.

The colour scheme is the standard four colour camouflage that almost all French aeroplanes wore at the beginning of the war. Modelmaster makes pretty good representations of those colours but it seems the French were a lot less rigorous than the Germans when it came to specifying which dab of paint went where so it would be best to have references of the particular aeroplane you’re modelling to be absolutely sure of getting it absolutely accurate.

The old Aviation News plans and colours of the 63.11 give quite a different camouflage arrangement than the kit instructions but, since I had nothing to replace the kit decals, I did what the kit suggested. Sticking all the additional pieces onto the model after it had been decalled was easy, the kit comes with a rear cockpit cover that folded back for the gunner, but I couldn’t find any photos of it in place so apparently it was often dispensed with in the field, so I did that too.

The end result is an odd looking aeroplane. You can see that once it would have been quite elegant but something went wrong with the new nose and it looks oddly cumbersome. Still, that’s the French for you, haute cuisine one moment and croque monsieur the next.

Leigh Edmonds

November 2003