In 1930 the French Service Technique de l’ Aéronautique issued specifications that would give the air force a new fighter capable of matching anything else in the air. In typical French style eleven basic designs were selected for development and a total of thirteen prototypes from ten different companies were eventually built for the competition. Almost every design concept and conceivable configuration was included among the contestants although most were powered by the Hispano Suiza 12X supercharged engine that offered sufficient power to meet the performance specifications.

Emile Dewoitine submitted two proposals, one for the 560 that was a development of the existing 370 series parasol fighter and the 500, a low-wing cantilever monoplane of essentially simple construction that was very manoeuvrable, stable and had exceptional aerodynamic qualities. It combined several design innovations that had been tried individually in other aeroplanes but never before in one aeroplane, most notable the single spar cantilever monoplane wing and the all metal construction. It was designed as the smallest airframe that could be constructed around the Hispano Suiza engine and it was selected for development for service. For its time it possessed exceptional performance because Dewoitine had considered the design specifications mediocre and aimed at offering something much better. As a result the specification was rewritten to, among other things, increase the top speed from 325kmh to 350kmh and the 500 did even better than that.

The prototype 500 made its maiden flight on 18 June 1932. In the tests that followed it demonstrated exceptional performance for its day and showed it was a well-behaved and extremely manoeuvrable fighter under most circumstances. It’s most serious weakness was its relatively high landing speed due to its clean design and lack of flaps or other high-lift devices. In November 1933 orders were placed for 50 Dewoitine 500s and the first production aeroplane flew on 29 November 1934, by which time orders had been placed for a further 130. Because of Dewoitine’s limited construction facilities most were manufactured by Loire et Olivier. They began entering service in April 1935.

Well before orders were placed for the 500 development began of a version powered by a Hispano Suiza engine capable of mounting a 20mm cannon between the engine banks firing through a hollow propeller shaft, and it entered service as the Dewoitine 501. Another version with a more powerful engine, the Dewoitine 510, began development in 1934 and was ordered into production in 1935. Had France gone to war with Germany over the militarisation of the Rhineland in March 1936 the Dewoitine 500s and 501s would have outclassed their German counterparts but the pace of fighter development was so great that by 1939 the little French fighters were obsolete. Only a few were in service with second-line squadrons when war was declared and all had been retired to training roles by the end of the year.

Who could resist this delightful little French fighter? Those unfortunates who gain pleasure from criticising French interwar aeroplanes for their ugliness conveniently forget, or are perhaps unaware of, the Dewotine 500. I have to admit to being similarly ignorant of this lovely little machine until I came across the kit. As usual with many French aeroplanes, I had to do some basic research to find out anything about them but, in the case of the 500, it’s important place in aviation history means there has been more written about it than most French aeroplanes.

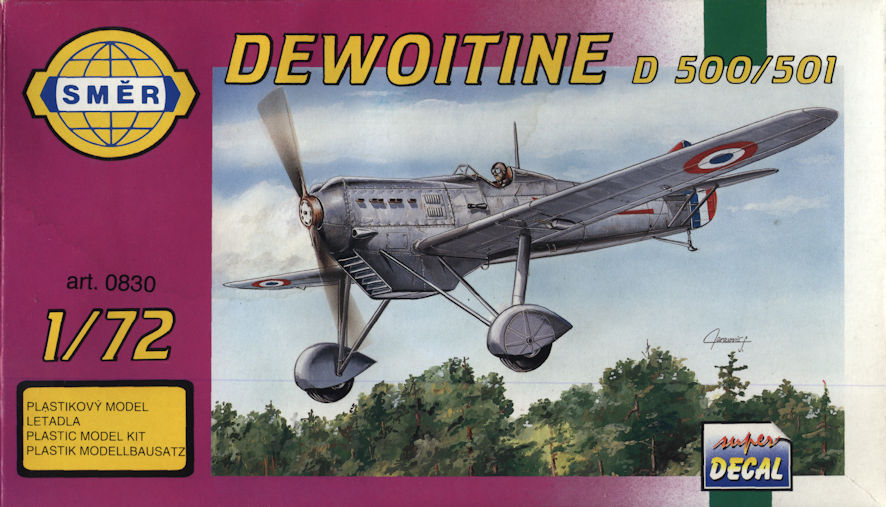

This kit originated from the French kit maker Heller and it is possible to find it in either Heller of Smer boxes. The only difference between then is the decal sheets and on that basis I’d suggest that perhaps the Smer kit is a little better. There are two versions of the basic kit, one is the 500/501 which gives you optional parts and decals for both and the other is the 510 which has a few more differences but uses many parts from the 500/501 kit.

Heller were at their best when they made this kit. It is not super-detailed as many kits from later manufacturers tend to be but all the parts necessary for a basic 500 or 501 are there. It is very finely moulded with slightly raised panelling that I sanded back a fair bit, still leaving a hint of some of the most important details including the wing spar. This is really a simple and accurate kit to assemble and it shouldn’t take more than a couple of hours to have most of the basic construction done. Strangely, the rear fins are butt joined which might be a challenge to some modellers. There is plenty of scope for improvement in the cockpit and the fit needs a little attention to detail in places. Getting the prominent radiator under the nose and the undercarriage to all line up properly is really the most difficult part of he whole operation. I replaced the radio aerial with a bit of stretched sprue of the right thickness more out of convenience when the antenna that is moulded onto one of fuselage halves got knocked off and disappeared into the carpet.

I chose to construct the 500 version because it offered some addition to the standard overall aluminium of the 501. The instruction sheet suggests the upper surfaces and the forward fuselage should be painted chocolate brown but the side view colours of this aeroplane, No.47, show it to be green. Other French fighters from this period including the Nieuport Delage NiD622 and the Dewoitine 371 are both green in places so I used that colour. This was yet another excuse to use the Alclad II I’d recently bought and it went on well and resisted handling and masking in a way that other products like Metalizer would have failed spectacularly. The end result is a delightful little model of an important milestone in aviation history.

Leigh Edmonds

September 2004