The battle between bombers and fighters defending their territory during World War II and in the early days of the Cold War led to rapid technological developments. During the war both sides had learned to their great cost that bombers could not fight off attacking fighters with guns (though they often discouraged attacks being presses home) but had to rely on the support of their own fighters or speed to reach their targets. The success of the deHavilland Mosquito showed that a bomber with enough speed could avoid defenders, over Japan the fleets of B-29s flying at high altitude had shown that while altitude wasn’t the perfect defence it was a great help. And then people went and invented the atomic bomb, developed the jet engine and made rapid advances in aeronautics. By the 1950s the supporters of strategic bomber were developing new, extraordinary aeroplanes such as the Handley Page Victor, Myasishchev ‘Bounder’ and the North American XB-70 Valkyrie. Their designers expected that their speed and high altitude would put them well outside the reach of defending fighters.

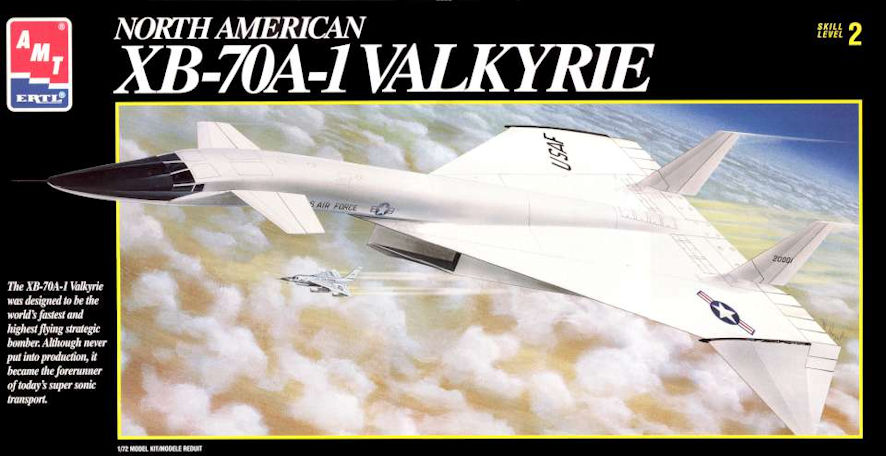

The most remarkable of these designs was the XB-70, which would have a speed of more than Mach 3 at an altitude of over 70 000 feet. To attain this performance North American designed a huge aeroplane propelled with six massive jet engines and wing-tips that folded down at supersonic speeds so the shock wave gave additional lift. Production involved many technical innovations and construction of three prototypes began in 1961, although only two were built.

The first XB-70A-1 flew for the first time 21 September 1964 and the second improved version (XB-70A-2) flew 17 July 1965. Even before they flew the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles and new generations of anti-aircraft missiles had rendered obsolete the whole oncept of high speed and high altitude as a means of defence. Even though they would never see service the XB-70s were invaluable in exploring many of the problems of high speed flight, in addition they where spectacular to see and hear so they made over 100 flights. The second prototype crashed spectacularly after a mid-air collision with an accompanying aeroplane in June 1966 but the first prototype continued flying until 1969, making many flights for NASA. It’s final flight was made in February 1969 when it went to the USAF Museum at Dayton.

It took me over two years to make this kit into a model that I am happy with. There were maybe three reasons for it taking so long. The first is that it is a model that I’ve always wanted in my collection, such a large and wonderful looking aeroplane was irresistible – for me anyhow. I had the very old Contrails vacform kit but it was so bad I couldn’t see how anyone could make it into a model that looked halfway reasonable. The second reason I took so long is because I don’t normally pay around $75 for a kit but for this aeroplane I made an exception. I wasn’t going to buy another one if I made a mess of it so I couldn’t afford to rush it. (I came across a couple of kits discounted to $35 in a hobby shop when we were passing through Port August in 199 but the car was so packed there wasn’t room for one, let along both.) The third reason was because it is not an easy kit to make.

For a while AMT produced a few very large aeroplane model kits including a B-52, Northrop flying wings (I found one for half price in the hobby shop in Albury and did have space in the car for it) and a C-135, but the XB-70 was their most anticipated kit. When it was released the reviews generally said that it was a satisfactory kit but be sure to buy in a couple more tubes of filler before you start work. Very funny I thought, ho-ho, but they were only half wrong, I only went through around one tube of filler getting this kit up to scratch. I don’t know whether any other manufacturer (Tamiya or Monogram for example) would have done a better job or whether the size and shape of this kit created the problems. In any case, it was a matter of trying to get the pieces to fit as well as possible, filling in the gaps and sanding back, putting on a coat of grey paint to see what it looked like, putting on more filler and going through the stages another few times. Some parts, such as the fuselage underside at the rear around the engine bay, just didn’t want to fit properly and in the end I gave up on it (I hope it’s not too noticeable).

After a year I’d got to the stage where I was more or less happy with the surface and then it was time to face up the big problem, which is that the aeroplane is white from one end to the other. Knowing how many coats of paint I’d need to apply to get a good solid white finish I figured that I couldn’t afford so much white modelling paint so I went out and bought half a litre of satin-coat house paint, thinned it down a lot and sprayed on more coats than I can remember, lightly cutting back after each coat. I used up most of the paint and worked away patiently doing a coat every week or so until I was happy with how it looked. Having got that far I put the whole thing aside for a few months for fear of messing it up in the final stages.

Finally I gathered up my courage and masked the whole thing for the silver and black areas, the masking took forever and the spraying only a few moments – that’s the trouble with masking, isn’t it? The main thing is the undercarriage which is aluminium, including the tyres that were impregnated with aluminium powder due to the heat built up during flight. (It looked very unnatural but I noticed in one photo that the wheels showed signs of greyness when they got a bit worn so I dry brushed on a bit of grey to give them a more real look). And then it was time to put on the decals (which went on nicely) and the whole ordeal was finally over.

Sitting back and looking at it, I’m happy with this model. The problems with gaps, vast areas of white, the desire to do a good job and the cost of the kit made it a less than enjoyable project, but the end result… Boy, is it white. And boy, is it BIG?

Leigh Edmonds

February 2001