By the mid 1930s most major aeroplane making nations were working on long range passenger carrying flying boats to equip their ‘flag-carrying’ airlines. For Britain and her dominions it was the Short Empire Class flying boats that also equipped Qantas Empire Airways from 1938. The flying boat had many advantages, primarily they did not need runways, just a large area of still water on which to land and take off, so they could fly almost anywhere there was a large area of relatively still water. Most nations also developed military flying boats that could be based almost anywhere without the need to construct large bases for them.

Britain’s Air Ministry drew up specifications for a long range general purpose flying boat in 1933 and Short responded with what was virtually a militarised version of the Empire-Class Flying Boat. The development work that had gone into the civil flying-boat allowed Short to offer a relatively sophisticated machine and, because the military version followed behind the civil version, it took advantages of the lessons learned in designing and constructing the civil versions.

Short won the contract to build the new military flying boat before the end of 1934 and the prototype Short Sunderland Mk.I first flew on 16 October 1937. They began entering service in December 1938 and 90 were produced before production switched to the Mk.II in August 1941 and then the much more numerous (456) Mk.III which was equipped with air-to-surface radar. The Mk.V was introduced in March 1944 and a total of 150 were built. They were fitted with 1200hp Pratt & Whitney engines that replaced the 1010hp Pegasus engines and the later ASV Mk.IVC radar that was fitted in two under-wing fairings.

The Sunderland enjoyed a long and distinguished record of service, sometimes doing exciting things (like sinking the occasional U-boat or driving off a hoard of enemy fighters with its defensive armament) but in general the Sunderland’s contribution to the war was endless hours spent flying long range patrols watching over convoys or scouring the seas for enemy shipping and submarines. They made an invaluable contribution to the allied victory in the Battle of the Atlantic.

A few Sunderlands flew with the RAAF, RNZAF and SAAF. A handful also flew with the French Aeronavale which took over a RAF squadron at Dakar in November 1945 and acquired 19 reconditioned Sunderland Mk.Vs in 1951. They remained in service until 1960, several years after they had been withdrawn from British service.

I must have made my first Sunderland model in the early 1960s and even then I did not think this was a terribly good kit. Big, you bet, but not very sophisticated by even the standards of the days and I never liked the fashion of moveable control surfaced, even then. Then there was the huge empty shell of a fuselage with absolutely nothing in it except a little platforms for a couple of pilots in the cockpit. Some time later I picked up another kit but I had no enthusiasm for making it, partly because of my memories of my first one and also because I didn’t find the colour scheme very appealing. So it might have been years before I got around to making it.

What happened to change my attitude was when I needed to order some airliner decals from overseas and I needed to buy something else to make up my order to the limit the shop had. While glancing through more lists of decal sheets I noticed one that offered a range of aeroplanes of other nations that also flew in French colours – it looked interesting and it pushed my purchase to just up to the limit and so I ordered it. When the sheet arrived it offered all kinds of enticing possibilities, a black Junkers Ju188, a Supermarine Walrus, an Anson, a Dornier and, most interesting of all, a Sunderland. At last here was something to make making a Sunderland worthwhile, and all the better because, apart from a couple of little bits and pieces, it was all over white from one wing-tip to the other.

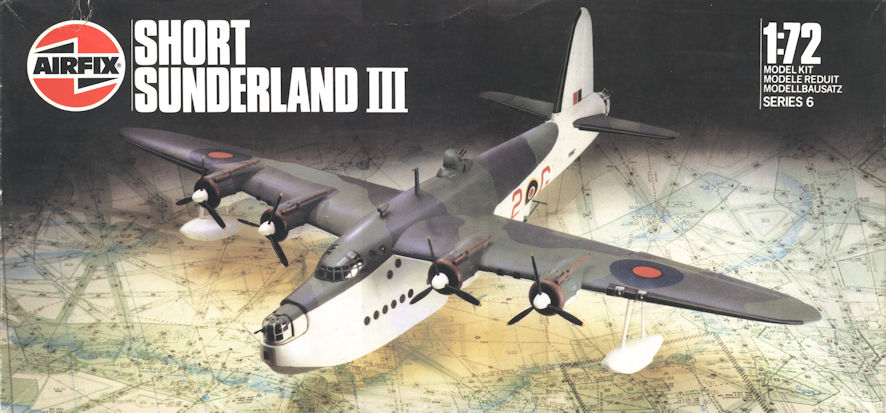

The problem that I didn’t realize straight away was that the Airfix kit offers a Mk.III and the French version was a Mk.V. I should have realized I was going to be making life hard for myself and that all the effort saved by the uni-colour scheme would have to be spent on converting the kit to a Mk.V. The basic difference are the engines, the propellers and the underwing radar housings. Fortunately I had a good 1/72 plan from an old issue of Aviation News that had some of the details of the Mk.V to guide me up the right path.

The first problem was the engines, if I couldn’t solve that it was back to the Mk.III in something British and dull. A pleasant morning shuffling through my kits found that the engines from the Airfix Handley Page Hampden fitted the Sunderland very nicely and looked a lot like the Pratt & Whitney engines while the propellers from the kit also suited the conversion. This meant getting and wasting two Hampden kits, but what are swap-and-sells for and anyhow. I’ll still be able to use one to make a Handley Page Heyford (for which a couple of discarded Sunderland propellers will work well. As for the underwing radar housings, the only simple solution was the balsa wood tricks I’d learned from Airfix Magazine back in the early 1960s and which I hadn’t used for decades.

Using the Aviation News plans it wasn’t too difficult to make two fairings that look more-or-less right and look more-or-less the same as each other. The same thing applied to the exhaust stubs for the new engines, eight of them that also had to be made so they all looked more or less the same. Being a bit small they caused me to inflict a few modelling knife wounds on myself, but they turned out reasonably well once I’d figured how to do them.

A lot of work and time went into getting the old Airfix kit to look halfway decent, including sanding off the thousands of rivets that infest the kit. Some problems like the turrets are more-or-less unsolvable so I just did the best I could with what Airfix supplied. The huge empty interior doesn’t look so bad painted flat black and the outside doesn’t look too bad painted white.

My real worry was how I was going to mask the 32 portholes but it turned out that my hole punch made little discs only a fraction of a millimetre larger than I would have liked. On went the French decals to give the Sunderland a touch of class and the end result looks pretty good, and big too.

Leigh Edmonds

February 2004