(Development of the MiG Ye-152 began with the Ye-150, a technology demonstrator optimized as a short range interceptor with a single Turmansky R-15 engine of 10150kg thrust, possibly capable of intercepting the U-2s that the United States had begun flying over Russia. Only one Ye-150 was built and it flew for the first time in 1958. Despite its outward similarity to the MiG-21 this new interceptor was larger and more powerful, and helped the Russians develop their next generation of interceptors.

In 1959 design work began on transforming the Ye-150 into an operational interceptor, the Ye-152 that flew for the first time on 10 July 1959. The operational version was to be powered by the large R-15 engine but that was still under development so the first prototype was designated Ye-152A and fitted with two smaller R-11 engines as an interim measure. Construction started on a second Ye-152A but it was used to build the second Ye-152 prototype powered by the single engine.

Flight testing of the Ye-152A concluded in August 1960 and it was then fitted with military equipment including the armament system with a ZP-1 radar, VB-158 computer and K-9 guided missiles. Testing the individual components of the interception system began in late 1961 and the fully fitted Ye-152A made 39 flights and fired 10 missiles during the test program. It crashed on 29 January 1965 during a test flight and the pilot was killed.

The more advanced single engined Ye-152M did not commence test flying until 1962. However development of an alternative design, the Ye-155, proved more promising and it became the MiG-25 while interest in the Ye-152 lapsed. Documentation on the Ye-152A (without engines, rockets and radar) was transferred to China which used the information to create its own interceptor, the J-8.

Despite it’s relative obscurity the Ye-152A became well known in the West. This was because it participated in the Tushino Air Show on 9 July 1961 and those air shows were about the only way that western specialists of the day could see the latest developments in Soviet aviation. The new aircraft was assumed to be in or nearing production and given the NATO reporting name ‘Flipper’.

This is the second Otaki ‘Flipper’ that I have attempted. The first time around I made a mess of it by trying to make the parts in the kit into something looking more like the original, but that proved to be impossible. This time around I built it straight out of the box – more or less – because it still looks more like a ‘Flipper’ than anything else, even though it doesn’t really look what you would call right.

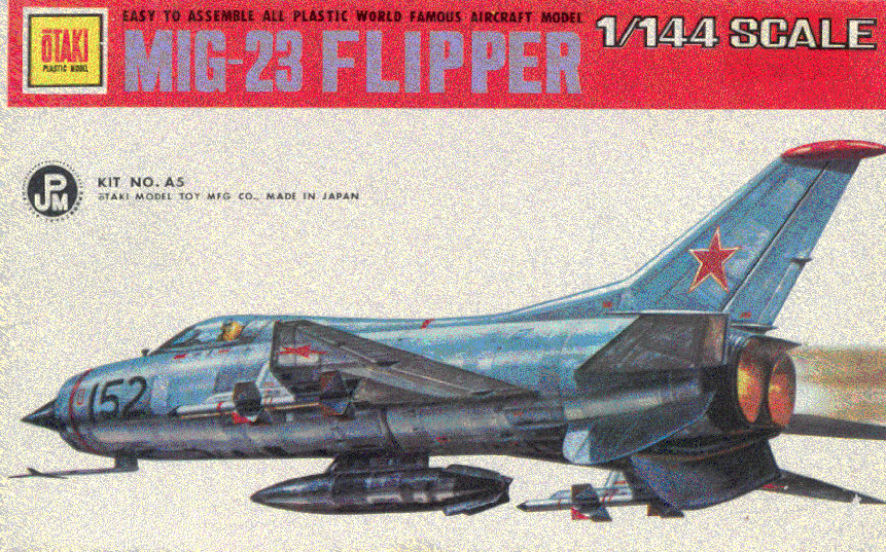

Don’t expect to find this kit lying around and easy to find these days, the price tag tells me that I bought this one at the Benalla Newsagency for $1.50 and I haven’t been shopping for kits in Benalla for decades (1985 would be the absolute latest) and the telephone number on the price tag only has six digits which puts it back in the stone age. My guess is that the kit was released in the early to mid 1960s when little was known about the ‘Flipper’, hence it’s mislabeling as a MiG-23 on the box.

Otaki made some quite good 1/144 kits in their time but it would be difficult to say that this was one of them. Part of the problem comes from the fact that people in the West knew next to nothing about the ‘Flipper’ for many years and the drawings that this kit was developed from show a few differences from later, more informed, drawings. Perhaps the most important is that the fairing running back from behind the cockpit to the fin is much smaller than shown in later drawings and in available photographs. In terms of overall shape the wings and the fuselage aren’t bad but the intake is not as large as it might be. Taking care of all these problems would make this kit a major undertaking, made even more difficult because the available drawings may or may not be accurate.

If there is one thing that could easily be done to make the kit look a little more like the original, it might be to take a couple of millimetres from all the undercarriage legs so that the finished model doesn’t sit quite so high off the ground. (I was tempted to do it but the plastic is somewhat soft and both main undercarriage legs broke off quickly and I stuck them back with little reinforcing pins. After that it was too late to cut through them again to get a better sit.)

The kit is simplicity itself and took only three nights to finish off. The kit took only a few hours to complete in reality, the delays were caused by waiting for the filler to set in the gaps, which are fairly impressive, and then waiting for paint to dry. The parts, what there are of them, do not fit very well so the kit took some effort in smoothing off the fuselage halves so they would fit fairly well and there was some careful surgery needed to get the wings to fit reasonably well. The intake and the exhausts were amazingly thick and needed some careful thinning, as did the fins on the missiles. About the only thing I did change was to cut the tops off the missile pylons , they include a wing fence that doesn’t appear to have been there, on the drawings I have anyhow. The nose probe was ponderously thick so I replaced it with a nice thin needle.

As for the painting; simplicity itself. A coat of grey to check that everything looked fine, a couple of coats of Metaliser aluminium, a bit of buffing, some dark grey for the wheels, white for the missiles and an educated guess of dark green for the nose. It didn’t come up looking too bad but perhaps more like a MiG-21 on steroids than a real Ye-152A.

Leigh Edmonds

August 2003