Long time readers may remember my Yakerschmitt, a totally fictional Me109 with an underslung turbojet, built for the sole purpose of confusing Luft46 fans. The trouble with creating fictional aircraft is that if you don’t do your research, you’re likely to recreate something that actually existed. These examples turned up as usual, after the project was finished. Fortunately, although the idea of of an underslung turbojet seems to have been considered, the idea of retrofitting current in-service aircraft was not. The Yakerschmitt remains totally faux.

My earlier effort was based on a late Me109, so it is only fair that the FW190 should also be upgraded. So as usual we need to look at what was possible given the state of the German Aircraft industry in 1945, and also what would be desirable to the Luftwaffe. One thing that springs to mind is the use of the FW190 as a dedicated ground attack fighter as in FW190F series. The early turbojets would have no advantage over a piston engine in that role. The Me262 was famously converted to be a bomber but was appallingly bad in that role. The main reason was that the turbojets ran most efficiently at high speed and high altitude. At a speed low enough to accurately deliver ordinance and a low altitude, the turbojets had severely reduced thrust. Another solution would be needed. Here the turboprop engine fits the bill. The turboprop weighed 40% less than a conventional motor of similar power. It also had the great advantage of creating its own high pressure area in front of the first compressor ring in the engine due to the thrust of the prop being in front of the engine. The engine can operate at maximum efficiency at any aircraft speed because the speed is determined by the pitch of the prop and not by exhaust thrust. A ground attacker could travel at low enough speeds to accurately deliver ordinance, operate efficiently at low altitudes and carry a much greater weight of fuel or disposable load. It also doesn’t need a 5 km long runway.

The earliest practical turboprop was developed in 1938 by Hungarian engineer, György Jendrassik, although the turbo-prop had been theorised as early as 1927 just the technology didn’t exist to build the designs. The Hungarian design was the first that actually ran and it was planned that this engine would be installed into a ground attack aircraft by 1941. This aircraft was subsequently cancelled. It would be reasonable to assume that the technology was also known to the Germans although no attempt was made to utilise a turboprop in any design. (Or the data has been lost). Post war Russian developments by German engineers indicate that the Germans were well advanced with development of a turboprop engine.

At the end of the war the Russians removed as much of the German aero industry as they could and shipped it back to Russia. This included 950 engineers and over 1000 railcars full of materials, tooling, machinery etc. The value of the engineers was not immediately realised and most ended up in the Gulag with Russian engineers taking over the development of the German turbojet engines. This would not prove to be overly successful because the turbojet required more advanced metallurgy than the Russians were able to produce. The turbojets had reached their limit in terms of power and reliability and engine life was poor as a result. This was solved in the short term by acquisition of the centrifugal Nene from the UK. Development of the turbojets was put on hold until someone had the bright idea to produce a turboprop as this type of engine was seen as having application for the new designs of heavy long range bombers then being proposed. (That would result in the Bear). A BMW018, was modified by installation of a propeller kit in a very short time. Whether the kit was amongst the German equipment or whether it was newly designed by the German experts is unknown. What is known is that the previously unreliable 018 was greatly improved by the addition of the prop and could now produce large amounts of thrust reliably as top end revs could be limited solving the compressor blade shedding problem. The prop also produced a lot of high pressure air immediately in front of the intake giving good low speed performance. It is theoretically possible that this modification could have been done in 1945 to produce an engine of approx 3500hp.

By the end of the war FW-190s were carrying enormous weights in relation to the size of the airframe. The later models could carry as much as an early B-17. A FW190 with a turboprop of 50% greater horsepower and at 0.6 the weight of the radial would be capable of carrying and enormous load, limited only by the wing loading. If the disposable load was also capable of producing lift, the load could be well above the weight of the aircraft. Hence a bomb with wings such as a Hagelkorn radio controlled glide bomb or a V1 might be a suitable load.

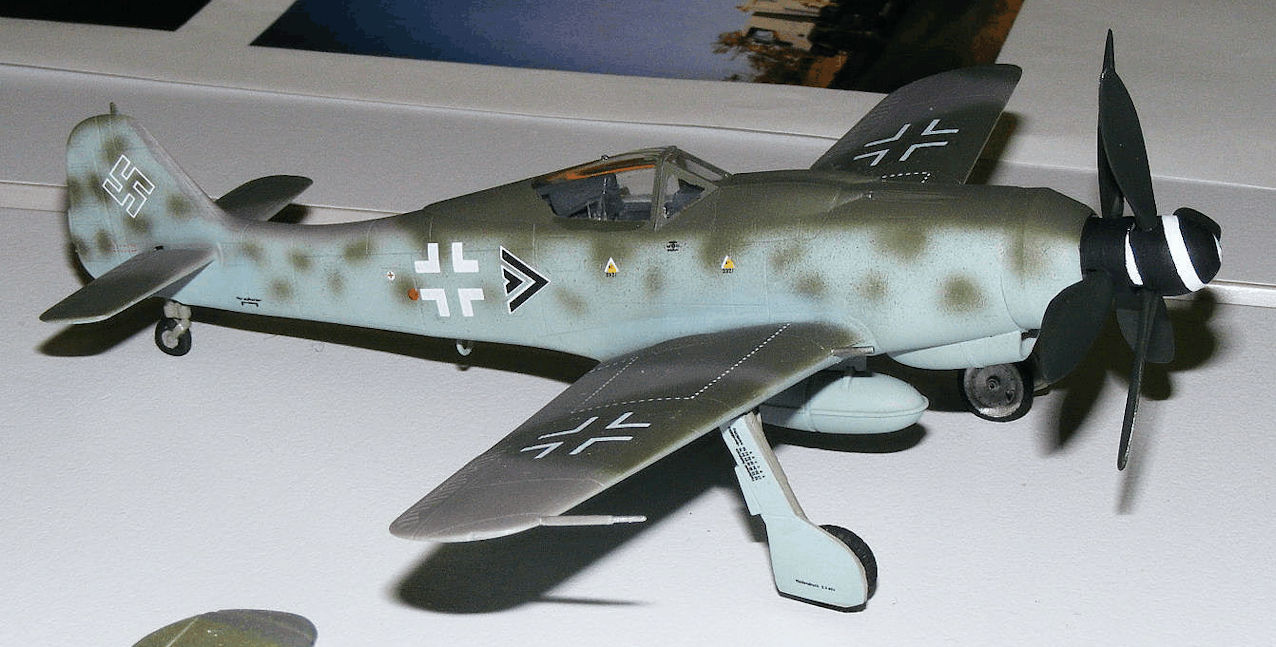

Turboprop engine aircraft generally have some stability issues due to the turning mass of the turbine rotor. This is usually addressed by either gearing the prop to turn in the opposite direction from the rotor or by using a contra-rotating prop. I decided a contra-rotating prop using the original paddle blades would look more German than a regular shaped prop. Adding 2 props would not be without it’s problems on the real aircraft. Every gun on the FW190 fires through the arc of the prop. Adding an extra blade would reduce the rate of fire available. A contra-rotating prop is a little more complex that a single prop. The contra props need to be geared not only to each other, but to the airframe as well. (Otherwise both props might spin in the same direction). This means that the point at which the blades cross can be designed so as to minimize the effect on rate of fire. Even so, the guns on the engine cowling would be obstructed for a significant amount of time.

The exhaust is another area that differs from the usual requirements for a jet. In a normal jet the exhaust is designed to provide thrust but in a turboprop, the work is done as the airflow passes the last rotor as this is what is geared to the blade. After that point, there needs to be no back pressure so the air is usually channelled out by the quickest means. In practice, the early turboprops quite often had angled exhausts that vent to only one side of the aircraft. (Modern turboprops may have up to 40% of thrust from the exhaust for good high altitude, high speed performance).

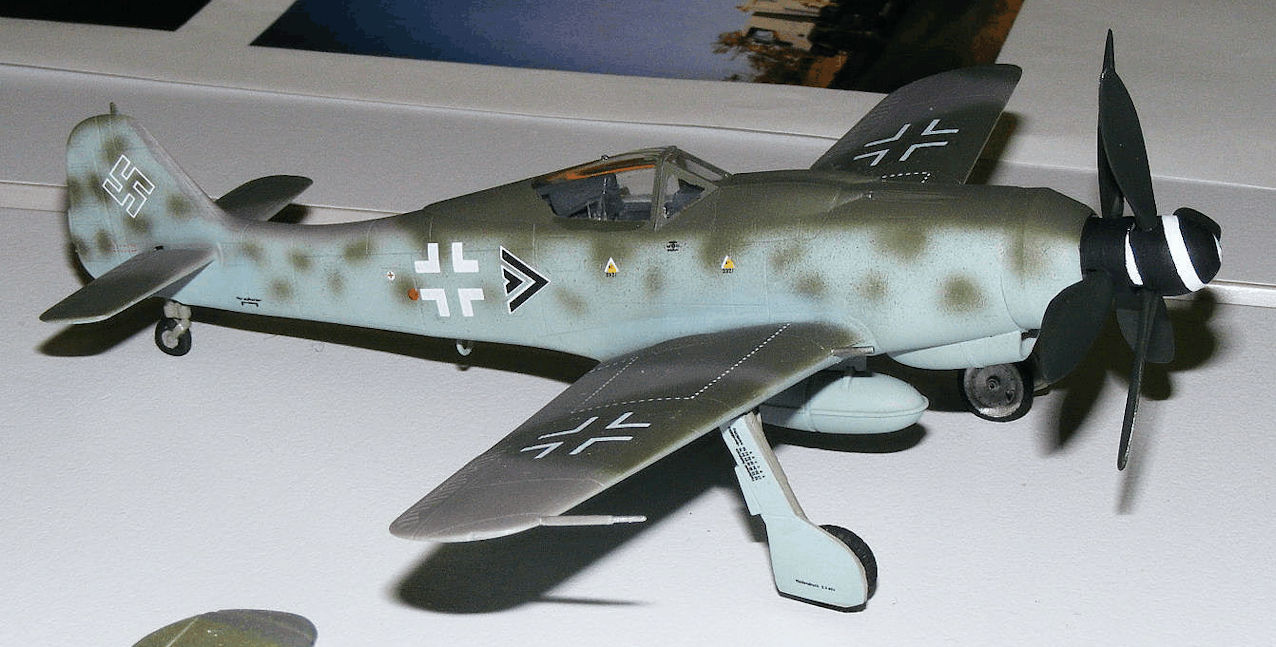

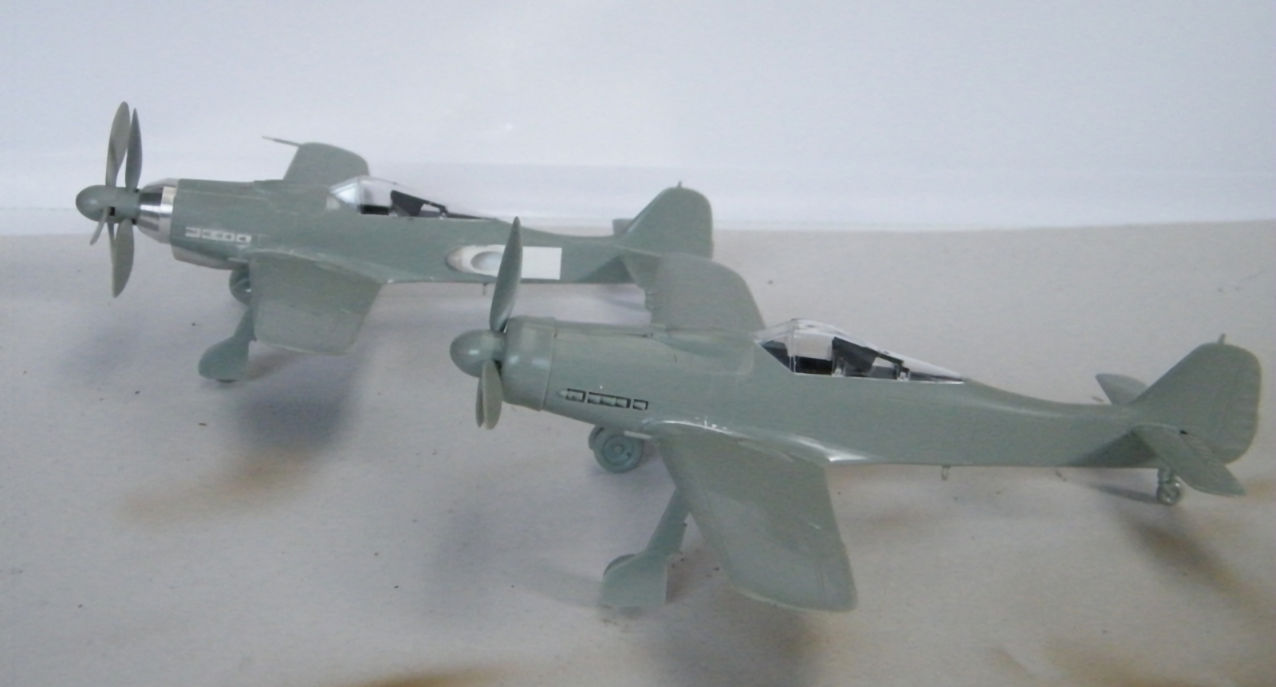

To build the model, an Academy FW190D was selected having the advantage of being cheap enough to butcher and having an extended nose and fuselage.. Applying both of the above considerations to the FW190D was quite simple. A new cowl was turned up on the lathe and an air intake placed under the nose. The existing exhausts were shaved off and the indents puttied over. A second prop was added with the blades reversed in a spinner that was cut down to the point just before it began to taper. A lump of tube was angle cut and inserted into the fuselage just behind the cockpit. These modifications are not too outlandish and not too noticeable to the untrained eye.

Hopefully, anyone familiar with the aircraft will have a WTF moment.

Steve Pulbrook

December 2011